This is a retrospective of my generative art project, Canvas Cards. Canvas Cards is a gallery of card designs created with the HTML Canvas element and JavaSript. I added a new card every Friday in 2019, and the site includes an editable code block for each card. It was hosted by Glitch, so the entire project is open for viewing and remixing. You can view the full output as a poster and the raw files and my tools in the Github repo.

I thought it would be worthwhile to reflect back on the process and my experience now that the project has concluded. This post is divided into the following sections:

- Why this project

- Interesting choices I had to make

- Tools and the site

- What it’s like to build a card every week

- My favorite cards and miscellaneous notes

My Introduction to Generative Art

I don’t remember what the first piece of generative art I saw, but it must have been in college because I had a brush with Processing, the popular tool for computer artists and creative coders. Whatever happened then didn’t really work out cause I had essentially no practical knowledge about programming. By the end of senior year, I had used Processing to generate some small charts that can be see in my Life of the Data Mind project.

Fast forward a couple years and I was having brief encounters with generative art mostly through Twitter. Things came to a head near the end of 2018. My work was kind enough to let me taking coding classes as part of my professional development, and I completed some basic React training. Then I encountered #plottertwitter— one of my favorite places on the internet now. It brought me inspiration and introduced me to the resources I needed to start my own project. The first was Matt DesLauriers’ course on Creative Coding with Canvas & WebGL, which was a nitro boost to my coding abilities. The second was Sher Minn’s History of Computer Art which sent me on a deep Wikipedia journey to read about early computer artists.

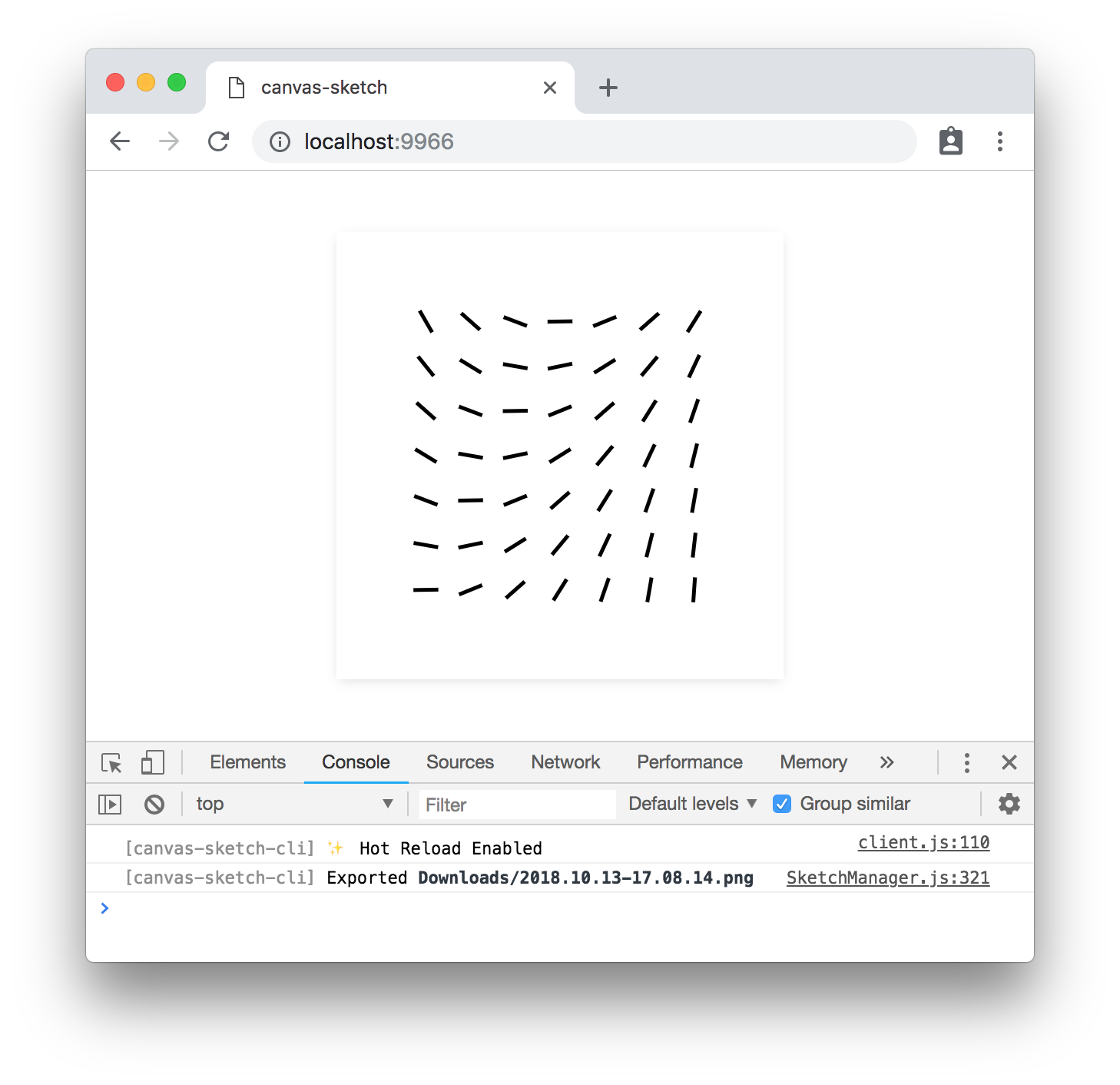

It was in this cauldron I decided that I wanted to create some generative art too. An AxiDraw pen plotter was too expensive and too large for me to get started with so I took Matt’s course and was introduced to his tool canvas-sketch. I produced a couple simple images following his instructions and using some of the included templates. At some point I read Inconvergent’s essay on generative algorithms and it crystalized for me that I needed a structured way to practice.

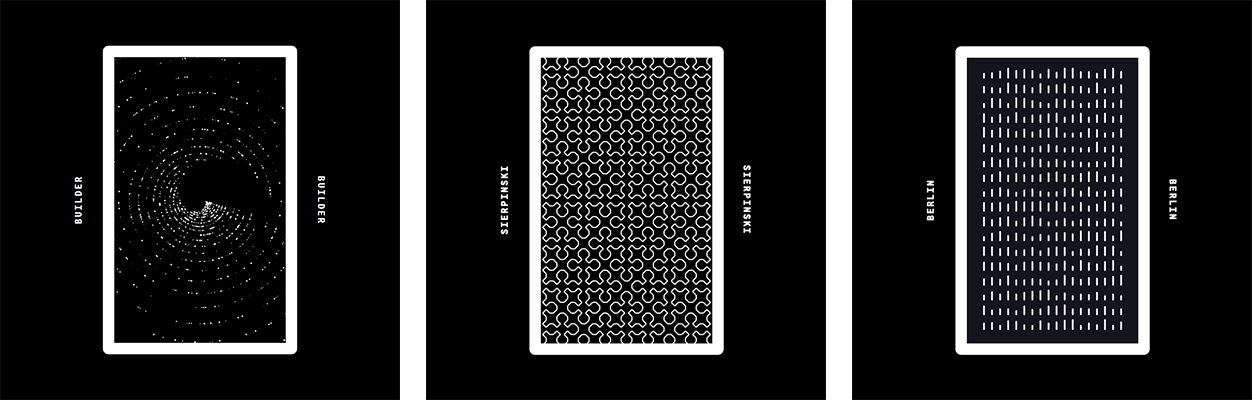

Canvas Cards

When I was in school, I was not very good at traditional art (and I’m still not). But I internalized the lessons they taught me about practice and improvement. If I really wanted to make strides in generative art, I needed a challenge that would (comfortably) stretch me and make me seek out new ideas and methods. It was a CSS tarot card on CodePen that first introduced me to the card idea, and I combined it with the default canvas-sketch template.

As I dug in a little bit, the details seemed to line up perfectly. It would give me a decent-sized canvas to work with and could pretty easily form a gallery. 52 weeks in a year, 52 cards in a deck and almost limitless visual potential.

Constraints & Ideals

Limitless potential aside, I knew it would be important to set up some boundaries for the project to make sure I was sticking to my guns. One of the best lessons I’ve learned in my design career is that sometimes limitations can spark uncommon thought patterns and creative solutions.

Some of the boundaries were simple, like publishing a new card every Friday. Others of them were philosophical, like making the entire project open source. I had already benefited immensely from people sharing their knowledge and code, so I wanted to make sure that I paid it forward and made my cards accessible for anyone interested in learning. In the same vein, I set some technical limitations to keep it beginner-friendly.

My full list of constraints:

- Publish a new card every Friday

- Cards are static images, as if they were printed

- No libraries or dependencies in the cards

- Everything is open source

Tools and Gallery

One of the most fun parts of the project was setting up the gallery site and my card builder. I knew I didn’t want to re-implement canvas-sketch in a browser, since it’s built more as a tool for exporting static images, so I would need to develop my own tooling.

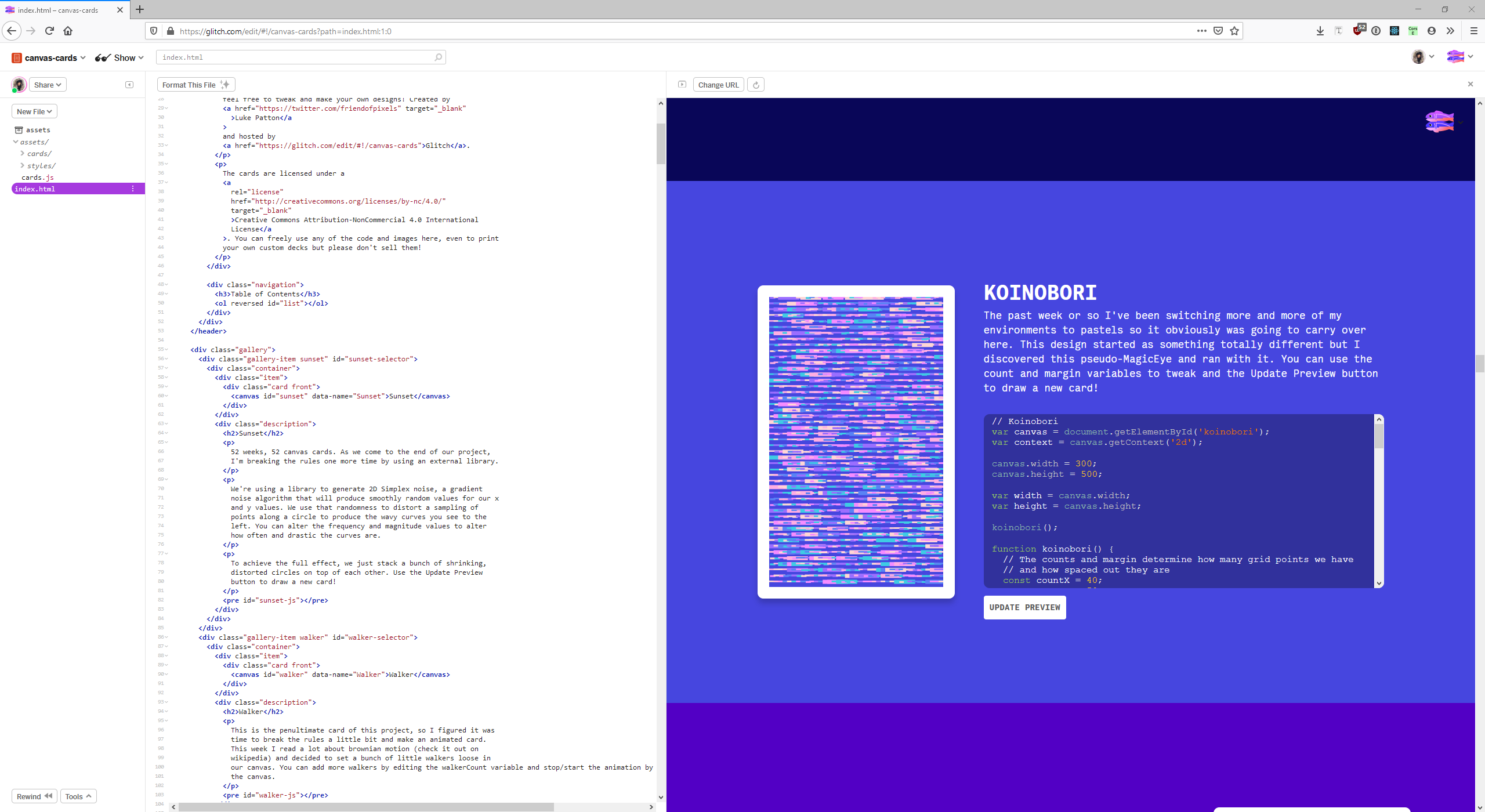

Gallery

I knew I wanted to host my gallery on Glitch pretty early on for a variety of reasons. One, it was dead simple to stand up with my requirements. I needed a single page, a single stylesheet and some JavaScript. I experimented with a couple layout ideas but settled for the vertical scrolling grid with alternating sections. Midway through the year, Glitch even released a VS Code extension that let me update the site directly from my IDE. Neat!

The big piece of JavaScript on the page is the one that assembles the table of contents and loads the cards. 52 separate requests is a lot of requests, so we use the Interaction Obsever API to only load a card when we come in contact with its canvas. Definitely one of the things I’m glad I set up early.

The code blocks were something else I knew were a requirement and a friend recommended I check out CodeMirror. To say it’s well supported would be an understatement, and it allowed the customization I knew I would need to make it fit into the site. For each card, we load its source code into a CodeMirror instance and tie its id to the “Update Preview” button. That button evaluates the code in the instance and loads it into the canvas. This lets us easily redraw cards that have generative elements and lets visitors easily test their own changes.

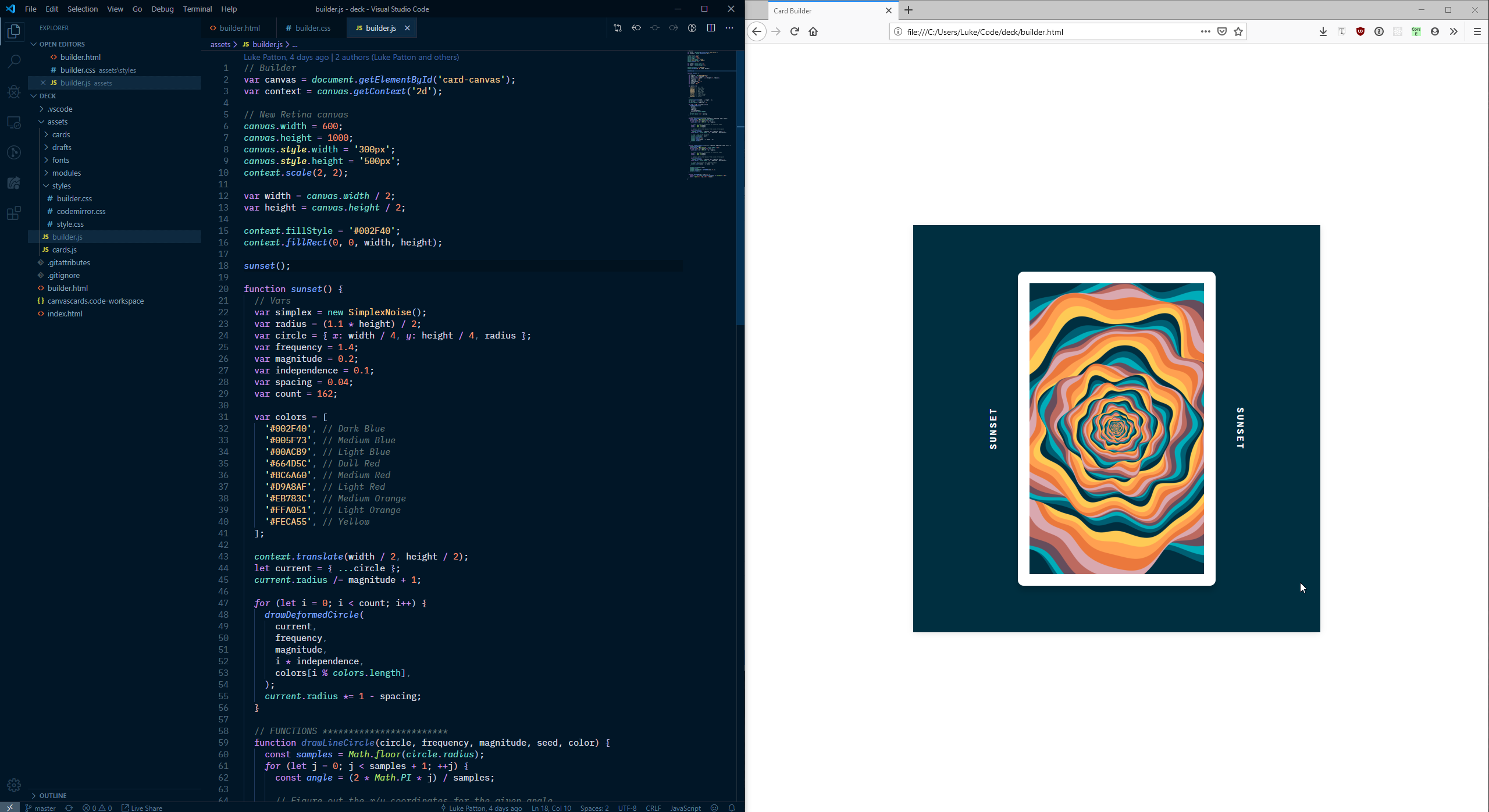

Builder

The other half of my setup is the builder file, which is the easel I would use to draft up each card. It’s a very simple file that just contains the card and its title in a box for easy development and screenshots. All the preview images were taken from the builder with Firefox’s built-in screenshot tools.

Making a card

So let’s get into the nitty gritty of how I actually made a card every week. One of the big keys was keeping my eyes open for interesting images and methods. I collected inspirational ideas anywhere I could find them. A lot of them came from Twitter and Tumblr, but I was also able to gather some inspiration in person from graffiti in my neighborhood, a sunset reflecting on some windows or the Plotter People meetup with other artists.

I was not great at math while I was in school, topping out somewhere in the Algebra 2 range. So sometimes the genesis for an card was, “I want to learn how polar coordinates work,” or, “How can you draw a shape with an arbitrary number of sides?” A particular example would be when Sher Minn brought a book to the Plotter People NYC meetup, Curve Stitching: Art of Sewing Beautiful Mathematical Patterns. Similarly to Sol Lewitt’s wall drawings, these pages were filled with instructions for constructing patterns.

// Pick 36 evenly spaced points around a circle

// Draw a line from n to n + 11

// Repeat for all points

These instructions were originally for sewing, but that’s practically already code ready for us to use. One of the most fun parts of generative art for me is grasping creativity with one hand and mathematics with the other.

Once the inspiration was stewing around in my brain, I would use an old design trick and not actually look at the image or photo again. I relied on my brain to remember what the interesting pieces of inspiration were and let the imperfect recollection guide me. Those raised edges of information were where I could jump off from and begin experimenting. I deliberately let the process be very loose—just throwing messy code around to see how different tweaks of the core idea would play out. Most cards started out in black and white, just to see if there was enough juice in the idea to be interesting.

Sometimes a card drastically changed over the course a week, and sometimes it emerged fully formed in an hour. As the project matured, I was also able to take pieces from previous cards and apply new methods and techniques to them for fresh outcomes. I kept a draft folder of half-baked ideas that I would raid for spare parts, sometimes months after originally jotting them down.

Once the card’s visual design was set, I would go through and clean up the code. This mostly involved clearing out unused variables, refactoring the main function and adding comments to help viewers follow along. After it was cleaned up, the card left the builder and was integrated into the main site with a descriptive paragraph.

Other Notes

My favorite cards

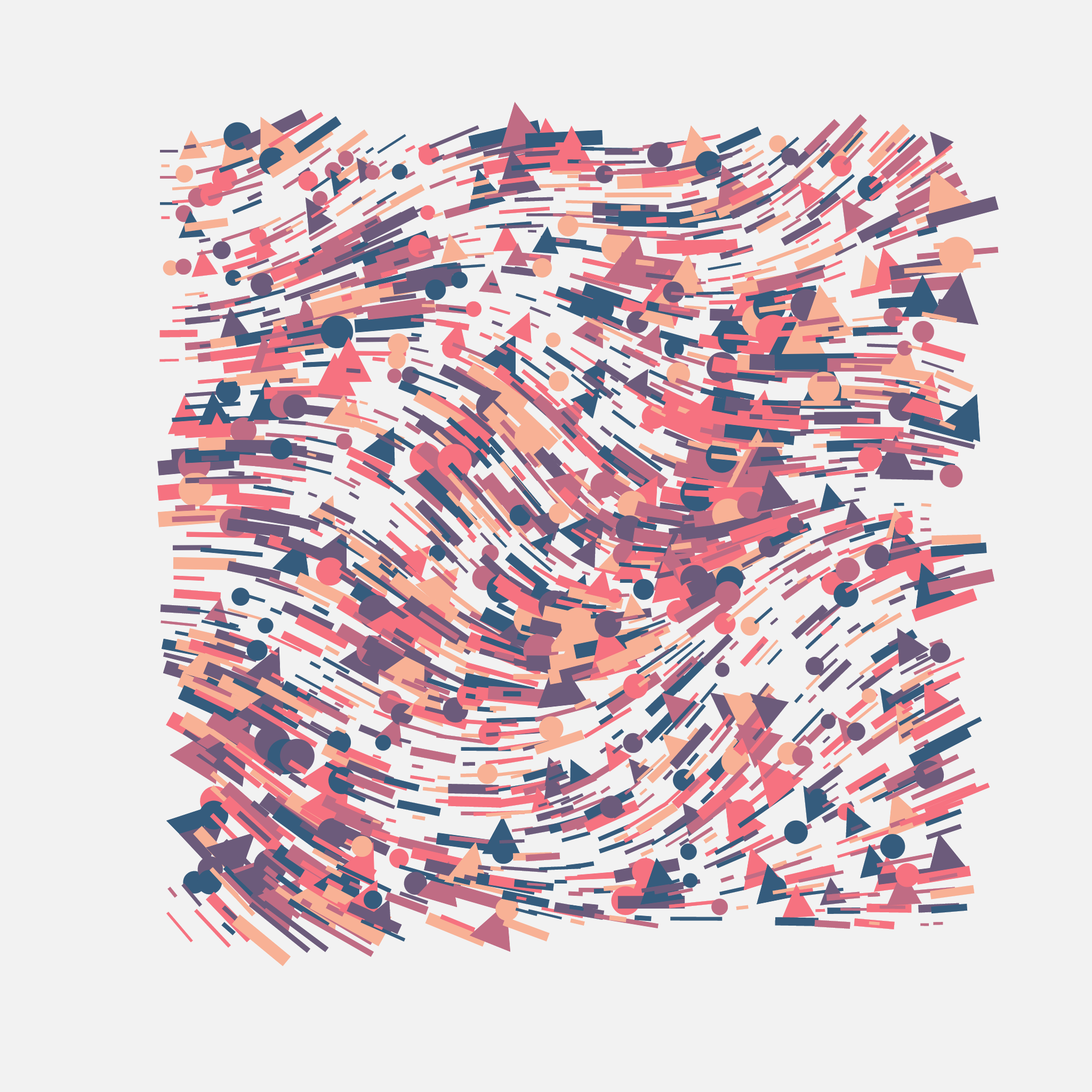

I love all my children equally, but I do have some favorites that stick out to me for particular reasons. In chronological order:

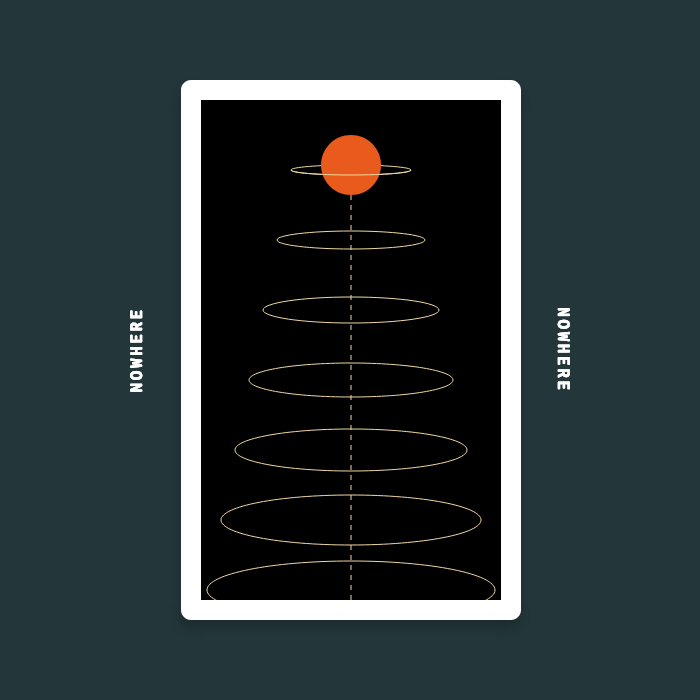

006 — Nowhere/Tomorrow

This was the first card that used some unorthodox techniques for drawing, even if it’s not truly generative. I saw a similar image on a comic book panel that a friend had as part of a screensaver. We use just a little math to angle the ellipses and a sneaky half elipse to give the ball a 3D effect.

016 — Boxer

There’s a lot about this card that shouldn’t work, but I think it does. A weird, mish-mashy quilt of colors and gradients, I think this was one of the first successful truly generative cards and it’s still one of my favorites to revisit.

027 — Corvus

I picked up an astronomy book in the gift shop of the Charlotte Mint Museum that detailed different constellations and fell in love with their style immediately. This is my little telescope and star field.

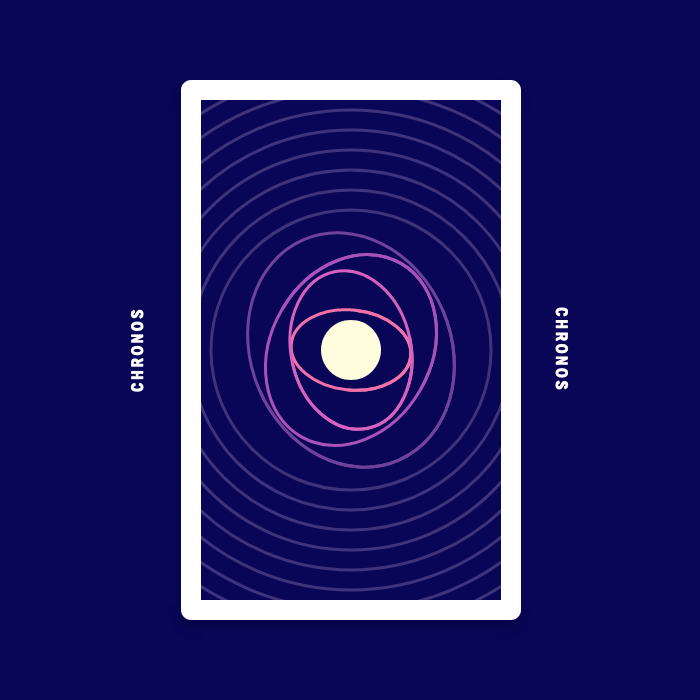

035 — Chronos

Chronos is the first card to use a data source to render its image. We use the data to set the positioning of the inner four rings of the card. From the inside out, the position and rotation is set by the current second, minute, hour and day.

049 — Datamosh

Years before I learned anything about generative art, I had seen examples of pixelsorting, using an algorithm to compare the numerical values of two pixels and move them accordingly. It was literally a dream come true to be able to implement it in just JavaScript and pixelsort in real time.

Personal Projects and Money

Over the course of the year, various people have reached out to me with financial offers. Some of them were kindly and wanted to know if there were posters or printed versions of the cards they could purchase. Some of them were representatives of digital art marketplaces that somehow traded ownership of artworks for cryptocurrencies? I didn’t really understand them, but I told them what I told everyone else, that I wasn’t interested in commercializing the project. Some people on Twitter thought this was strange, as if I was leaving money on the table by not commercializing the project. I ended up adding a Creative Commons license to the project to make it clear that the cards were never to be sold.

To me, the introduction of money would be would instantly change the dynamic of creation for the worse. I would no longer be doing a project for myself and for a community, I would be someone with something to sell. I similarly don’t make my friends and family pay me to touch up their resumes or design their wedding invitations; the money changes the dynamic in uncomfortable ways. In the future, I might offer a poster print of all the cards, but no promises.

Do It Yourself

I’ve been fielding a decent number of questions from people interested in generative art and canvas experiments, so I figured I would collect some of the resources that I used during this project (some of them might be linked earlier). This is assuming at least a passing familiarity with HTML and web tech.

Beginner:

- MDN’s Canvas API Tutorial

- The Coding Train

- Wes Bos’ Beginner JavaScript course

- Why Love Generative Art

Intermediate and Generative Art Specific:

Advanced/Theory:

- Computational Drawing: From Foundational Exercises to Theories of Representation

- The Book of Shaders

In Closing

As I was writing this post, I told my wife that I feel creatively energized having finished this project. It’s been amazing seeing the positive reception and talking to people about generative art. About 10 weeks in, I thought that I would never find enough ideas to fill the year but it soon became apparent that I had nothing to worry about.

I don’t have concrete plans for what I’d like to explore next, but I want to return to some of the more advanced tools for drawing and try to produce some physical works. If you have any questions about the project, you can contact me on Twitter.